When adapting famous novels into plays, the debate-and often the source of disappointment-is choosing what to cut. Elevator Repair Service has made the boldest, and yet at the same time the most neutral of choices in their adaptation: they have staged a production of F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s “The Great Gatsby” that includes every single word of the novel. As you might expect, this makes for quite a lengthy piece of theater. The entire show runs 8 hours, with two intermissions and a dinner break, placing it among the other gargantuan plays of the past year (ANGELS IN AMERICA HARRY POTTER AND THE CURSED CHILD, or to a lesser extent THE ICEMAN COMETH and THE FERRYMAN).

While all of these are quite long and large in scope, something about GATZ feels incredibly intimate and unique. Where else can you see an entire novel, every single word, play out on a stage, let alone a novel as legendary as “The Great Gatsby”? Fitzgerald’s iconic 1925 novel is a ubiquitous part of American culture and its portrayal of the Roaring 20s still impacts our conception of the era. However, this production of GATZ is nothing like you would expect and is nothing like either of the famous film adaptations. There’s no flapper dresses, no champagne flutes, no old cars.

Instead of focusing on the visual and aesthetic glamour of “The Great Gatsby,” GATZ puts all the emphasis on the words, on Fitzgerald’s poetic prose. Sure, the dialogue is iconic-who can forget “I loved you too” or “Gatsby? What Gatsby?”-but is its Nick’s silent thoughts to himself that make the novel soar, and they are exactly what has been missing in previous adaptations.

GATZ signals to the audience right away that this is going to be more about words than visuals: the set (designed by Louisa Thompson) is a bland, outdated office. At rise, several employees enter, in modern, boring office attire (costumes by Colleen Werthmann). They silently go about their work for quite some time. One employee’s old computer won’t work and he struggles with it, continually resetting it. He eventually gives up when he finds a copy of “The Great Gatsby” on his desk and begins to read it aloud, clearly annoying some of his coworkers. Although it seems rude and unfathomable, he just keeps reading. Here it becomes apparent to the audience that he is not going to stop, that this is the show.

But then something magical happens, while he reads the first chapter, other coworkers begin to slowly transform. A woman in the office starts reading a golf magazine. A service worker takes the computer away for repairs. A female lounges on a couch. A hulking man angrily reads mail. Although our reader (Scott Shepherd), who here stands in for Nick, initially does all the dialogue himself, soon the coworkers join in, each assuming their role of Jordan the golfer (Susie Sokol), George the mechanic (Aaron Landsman), Daisy the debutante (Tory Vasquez), and Tom, her cheating husband (Pete Simpson). This transition is shockingly smooth. To help, we never fully go into a production of “The Great Gatsby;” it always clear that in at least some realm of possibility, these are all still just coworkers putting on a bit of a show. Only Shepherd reads from the book, everyone just miraculously knows their lines, they are all somewhere between an office worker and Gatsby characters.

Part of what makes this liminality clear is that the actors are not really acting as much as they would if this were a regular staged adaptation of the novel. They have the essence of their characters, but everything feels a bit more casual, a bit less dramatic; everything has an aura of an understatement. For the first few hours, this makes the major plot moments and iconic lines feel a bit underwhelming and gave a slight indication of potentially unclear direction by John Collins. In a similar vein, several major moments, instead of being high stakes and stuffed with emotion, are played for laughs, as if this whole thing is employees doing the scenes for fun instead of characters going through crises.

The comedy, however, breaks up what otherwise at times feels a bit never-ending (the dinner break was also a much need restive). In a play that runs 8 hours, it is no surprise to hear that it felt very long. The show certainly has lulls and less interesting sections, but immense praise has to be given to the expert and adept team of actors for maintaining energy for such a long performance-especially Shepherd who speaks almost constantly.

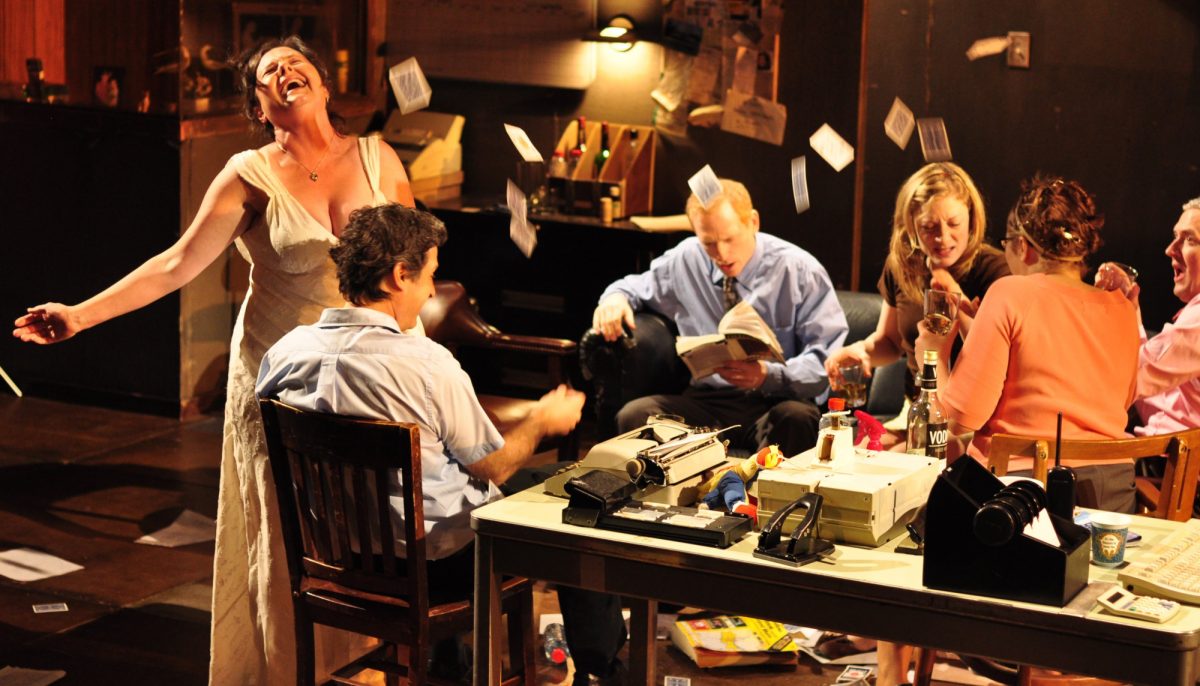

Part of what makes the play not fly by was the static nature of the design. The office environment, which is clearly important to the dramaturgy of GATZ and is brilliant in some aspects, can feel monotonous (and perhaps it is supposed to). We are never given a set change, the most dramatic thing to happen is a chaotic throwing of papers and playing cards during the party Myrtle (Laurena Allan) throws in New York. Ironically, her small gathering has more of a dramatic set change than any of Gatsby’s legendary soirees; in fact, for the first Gatsby party Nick attends, the party guests on stage (a small number, since the cast here, is only 13) spend the whole time cleaning up the paper from the previous scene, not doing the Charleston and drinking, as would be expected and as Nick describes in his narration.

At times, the dissonance between the narration and the lack of stage visuals and actions was powerful, but at other times it felt odd. The costumes contributed to this inconsistent dissonance; some actors bizarrely and randomly donned outfits mentioned in the narration (an evening gown made a brief appearance, as did Gatsby’s white linen ensemble and his famous pink suit), while other stayed in modern office attire.

Despite the length and sometimes incongruous design, everything comes together in the final act in a way that is equally unexpected and extraordinary. Shepherd (or should I say Nick?) puts down the book and does the last act from memory, an emotional and effective device. Here, our reader falls deeper and deeper into “The Great Gatsby” and the line between the office and novel becomes increasingly blurred. As he recites the final, tragically beautiful pages of the novel, all of his coworkers pack up, turn the lights off, and leave the office for the day. Maybe this was not some magical pop-up production at all, but just an employee staying at work all night reading an American classic. Shepherd here proves himself to be an astoundingly impressive actor, perfectly capturing the poetry of Fitzgerald’s prose.

In this last section, the direction for the entire piece becomes remarkably clear and deeply thoughtful, proving that GATZ is a superbly beautiful slow burn of a production. GATZ is an unmissable, one of a kind experience, a stunning, extraordinary theatrical event unlike anything else. It is probably one of the most impressive and imaginative production you will ever see on a stage, a flawless translation of Fitzgerald’s beloved novel into a new medium in a way that is at once magical and masterful.