The last time we heard from Theresa Redbeck, she was writing for “Smash,” letting two major actresses embody and tell the story of an even more famous actress from the past, Marilyn Monroe. In a similar vein, Redbeck, in her new play commissioned by the Roundabout Theatre Company, gives Janet McTeer the opportunity to become Sarah Bernhardt.

Perhaps you don’t know who Sarah Bernhardt is, a confusion that is representative of the general problems of the play — it is often too historical, too dramaturgical, too smart. “Bernhardt/Hamlet,” currently playing at the American Airlines Theatre, tells the true story of a celebrity actress in late nineteenth century France who boldly chose to play Hamlet. In many ways, it comes across very similar to a Tom Stoppard play. While watching this piece I ironically kept thinking about “Travesties,” the Stoppard play that Roundabout produced in the same theatre this Spring.

Both plays are rooted in both literary and biographical history and assume the audience can follow along as they throw obscure references out left and right. What makes both play ingenious, however, is that they both parallel the structure of their source text: the language of “Travesties” mimics “The Importance of Being Earnest,” Dada poetry, limericks, and political manifestos. Similarly, “Bernhardt/Hamlet” is seemingly structured on “Hamlet” and its characters, plot structure, and most noticeably, its excessive talking and lack of action.

Although the device of mirroring the text the play is based on is quite creative from a literary perspective, from a theatrical perspective, it is not necessarily noticeable or convincing, unless you are very well versed in the original. To make matters worse, this type of play only works when the source text is enjoyable, like “Earnest,” but when you base a new play off of a lengthy, brooding, melancholic, overly poetic play, your are bound to bore the audience with too many “words words words.”

Throughout the play, Sarah and the other characters debate Hamlet’s age, women playing male roles, the concept of authenticity, sexuality, the poster design, and excesses of Shakespeare’s use of poetry in “Hamlet” — an argument that it seems dominates every single scene. The play seems to lack structural coherence: although most of the first act is “Hamlet” rehearsals, in the second act we spend more time with “Cyrano de Bergerac” than with the Prince of Denmark (Sarah had an affair with Edmond Rostand, another historical figure you probably haven’t heard of). Ironically, although this play expects a massive amount of background knowledge from the audience, it also deviates from the historical record, moving events around to fit the dramatic action. The most upsetting structural element, however, is the fact the after over two hours of rehearsal and debate, we are never given a glimpse of Sarah’s actual performance as Hamlet.

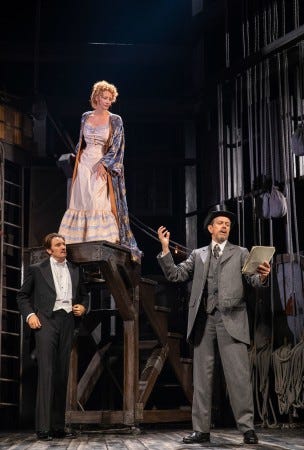

Despite all the plays problems, there is certainly a great deal to praise to be given, almost entirely to the extraordinary Janet McTeer. In this — and in all plays, she is in — it’s everyone versus her, and unsurprisingly, she wins. She commands the stage whenever she graces us with her prescience, which in this play was, thankfully, most of the time. Much like her Sarah Bernhardt, Janet McTeer has become iconic, legendary, and to use the title most frequently given to her character, divine. In late nineteenth century Paris everyone went to see whatever show Sarah Bernhardt was in, simply because they wanted to see her; over a hundred years later and we are doing the same thing, going to see plays just to be amazed at masterful acting by Janet McTeer.

One of the play’s central questions (there are too many) is not simply, can a woman play Hamlet, but why should a woman always have to play Ophelia? Are there not better options? In the strongest and most politically relevant moment of the play, Sarah goes on a rant against Roxane, the perfect embodiment of feminine virtue Rostand wrote for her to play in “Cyrano.” Roxane may be a man’s idea of perfection, or even a playwright’s, but she is certainly not the ideal for a woman or an actress. Sarah refuses to play the role, taking an amazingly feminist stance by arguing that playing ingenues is beneath all actresses; she says that women deserve better parts, roles that are as difficult, complex, and yes, wordy, as men.

If nothing else, Janet McTeer has here proven how true her line is: women deserve challenging roles, given them a chance and they will soar.