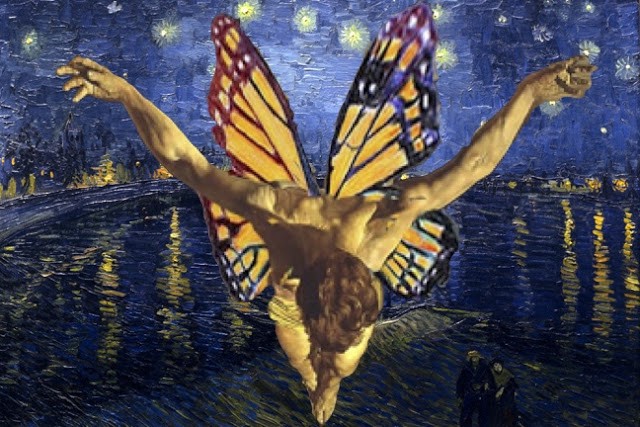

(“Steve” is a composite of some of the men I’ve met in recovery, some of whom committed suicide-by-relapse. Constructing this fictional biography is part of an attempt to figure out how inordinate physical beauty — a trait most of us envy — creates its own set of issues in relation to addiction.)

“Steve” grows up in a churchgoing Ohio family, one of three kids. He is just masculine enough to “pass” in high school, or maybe it’s the fact that the girls think he’s so cute. In college he starts to wonder if his attraction to men isn’t as “bad” as he was taught, though his first sexual forays –with his fraternity brothers — involve copious amounts of alcohol. This starts a lifelong association between sex and intoxication.

Steve can’t wait to move to the L.A., where he gets a real estate license and begins to hit the gym with fervor. He comes out to his family, but the topic is largely avoided after he does. He finds the competition at work very tough, and is relieved to land a job as a bartender. His head-turning looks make him an immediate hit, and he learns how to enjoy being the center of attention — a little easier when part of the job is letting customers buy you shots. After work one night, a co-worker offers him his first bump of crystal, but he turns it down. He sees how wrapped up in it some get, and doesn’t want to risk being whispered about. (Being a bartender has reinforced his burgeoning sense that who he is and how he is seen by others are one and the same.)

Steve has a series of casual boyfriends, but bartending doesn’t mix well with relationships. Besides, he likes to go out and always gets propositioned. On his days off, he meets guys at the gym or on line. On some level, he recognizes that the sex is far less important to him than the moment when they say they want him. The compliments even embarrass him a little, but he becomes addicted to hearing them.

One night he goes home with a porn star every inch a fantasy. He offers Steve some crystal, and this time Steve says yes. It’s the first time he has leather sex and engages in serious role play. The connection with this guy seems so intense and real. The crash sucks, but by the next weekend Steve is at it again.

The porn star is in an open relationship, and Steve can’t believe he’s letting himself get involved anyway. He’s also having unsafe sex, even though HIV hasn’t been discussed. Aside from the crystal, Steve starts doing steroids. When it’s suggested he do some porn, all of his buttons are pushed. It’s as if the more validation he gets, the more he needs. Steve slowly loses touch with what used to make him feel unique — that funny kid who loved to draw and wanted to be an engineer or architect

Steve calls in sick a few times too many at work, and they start to give his shifts away. To make ends meet, he starts working on the side as an escort. Soon the “new normal” is even more money and more attention. Now he makes his living straddling the divide between fantasy and reality. He can’t even imagine pulling it off without the meth. When he is high, he feels like the man his clients perceive him to be.

Eventually, of course, the meth stops working the way it used to. Steve is antsy and distracted on his calls, and his repeat clients drop him. His life becomes smaller and smaller. He spends hours on the computer, often hooking up with the same guys he used to dismiss as “tweakers” because they share their crystal with him. He gets a staph infection, and uses it to wheedle money from his mom. Thankfully his family flies into town and stages an intervention. By then, Steve is finally ready to enter rehab.

Let’s pause Steve’s story here, and take a deeper look at what was fueling his trajectory.

It’s easy enough to dismiss his behavior as narcissism run amok, but he’s just reacted quite rationally to a culture which treats extreme good looks as if they represent far more fundamental qualities. When you are physically “blessed,” people tend to ascribe a lot of traits to you that you may not have. It’s much easier not to work on yourself — emotionally, intellectually and spiritually — when a hard body and a winning smile get you all the strokes our society tells you equal happiness.

Many gay men are co-conspirators in this process. We flatter and objectify as we feel flattered by being objectified; we put the hyper-beautiful on pedestals and then wonder how they can fall off. We find it hard to imagine that if we had that face and that body, we wouldn’t have all the raw materials required to win the game of life.

This culture of validation results in a lot of men looking for answers in the mirror, or in the reflection of themselves they see in your eyes. What meth does is blur the line between self and image; it creates the illusion, momentarily, that you are entitled to all your good press. It’s an ersatz, chemically-induced authenticity, but it temporarily squelches the sense of being a fraud — and there is relief in that.

I’ve seen some of the most physically striking men imaginable relapse over and over in search of that moment the high gives them where they feel deserving of all those compliments. Ironically, it’s not far off from why those who don’t turn so many heads use meth – to give themselves a break from the voice inside that tells them their lesser looks make them a lesser person.

I’ve seen all variety of men stay clean, and they have one thing in common: they learn to measure themselves by that which is immeasurable—one’s capacity for kindness, love, compassion and forgiveness. These are things that never fade and cannot grow old, but always get better with age.

Physical beauty is not meaningless; but we evolved an appreciation for it mostly for biological reasons. Aesthetically-pleasing features and strong bodies represent healthy genes. We won’t stop wanting those who we want — nor should we try. But we can aim for a right-sized reaction to beauty, not attaching assumptions to it that are more projections of our own desire than anything else.