Art is a bit like marmite: you either love it or you hate it. Or maybe you just think it’s not for you. After all, there’s plenty of unflattering portraits of affected middle-aged gay men flaunting their passion for les beaux-arts. Better to stay well away. Better to avoid the suspicion.

But if we act as if art is something optional, we’re missing out on something potent. Art isn’t just for the obvious connoisseurs; it’s for everyone. I’ve always visited art galleries, but over the past year, I’ve upped the frequency of my visits. Traveling through Spain and France as well as checking out what the UK has to offer, I’ve learned how to view art in relation to my experience as a gay man.

Today is Sunday, and I’ve paid a return visit to le Palais Beaux-Arts in Lille — just over an hour by train from London. I also spent Easter here this year and took the opportunity to mooch around the gallery. This was a perfect accompaniment to my entrance into gay Lille, where, I’m assured, I’m a perfect likeness of France’s game-show host, Cyril Féraud.

Although there aren’t any explicitly gay artworks on display in the gallery, this doesn’t matter. There’s more than enough food for gay thought. Here’s how.

Look at sculptures

I’m sure many of us have wondered what life would be like if we never got old, if our faces never wrinkled, our bodies never decayed. Well, spend some time looking at sculptures.

When I walk around sculptures like this one, I begin to feel like Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray. I wonder what if the statue got old and I didn’t; somehow I would always stay the same. Granted: my butt might not be as firm as this twink’s; but it’s a fair likeness. The sheer effortlessness of this boy’s grace and bearing is palpable. Look at the arch in his back, the curve of his thigh, the twist of his shoulders. See how he leans to one side, his head lifted up in confidence.

And yet, what are statues like this really doing for us? Personally, I don’t think they’re 3D likenesses of real people. Instead, they’re idealizations, almost deliberately unattainable. This is a boy who has never spoken to us and never will. He has no agency; he is entirely superficial.

Looking at sculptures is a visceral experience. The warmth of our bodies brushes past the coldness of theirs. And yet, such statues express a deep sense that aging is a cruel process, something to be met with courage as well as grief. In the midst of celebrating the glories and beauty of vigor and youth, we are touched by our own experience that these things fade with time.

Watch out for allegories

An allegory is an artwork that contains a moral or existential message within it. Often the subject matter will be symbolic of this deeper meaning. There might be specifically gay allegories out there, but we can all benefit from broader ones.

This is a portrait of the Christian saint, Jerome, by Jose de Ribera. We don’t need to know that this is of a famous saint to engage with the subject matter. What I see when I look at this is an elderly man trying to face death. Partially-clothed, he lingers between life and death.

His furrowed forehead suggests that he’s deeply engaged with the prospect of his own mortality. And of course, this is something we all think about from time to time. In the throng of life, we’re all holding our skulls in our hands, incredulous that one day we’ll no longer breathe.

I’m not sure why gay men are particularly known for fearing the path to death, fixated on youth. But this could be a portrait of all of us over the age of 80, a poignant token of our mortality and a reminder to live as meaningfully as we can in the present.

Be open to the religious

Being surrounded by religious art can be an oppressive experience. We can feel as if a million tentacles were reaching out to catch us in our path, battering us with hand-me-down insecurities and fears.

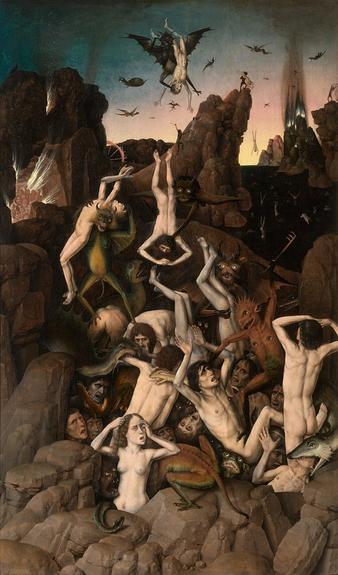

I don’t know whether you’ve noticed, but there seems to be a Catholic sensibility which depicts hellish torments through upside-down people. I’ve always been struck by seeing a sculpture of a soul in the clutches of the devil as a typical devil-like creature holding a naked man upside down. The implication is that the experience of hell is disorientating.

I pay attention to images like these because they depict in fascinating ways some of the unhappiest experiences we face in life. If ever you wanted to describe how you felt in the depths of depression, in the swelling of anger or the clutches of addiction, then maybe you’d paint a picture of yourself naked and upside-down — totally disorientated.

To my mind, this picture symbolizes the chaos of our dark nights, sometimes caused by our own choices but often just par for the course in life. When I look at this, I begin to reach out in sympathy to others, longing for something or someone to deliver us.

If hell is anything, it’s the realm of lived nothingness, where nothing and nobody makes sense, including ourselves — a feeling of abject loneliness and hopelessness.

Be open, then, to the religious in art. Maybe it will describe something specific to your experience. Don’t be afraid to make it your own.

I don’t know what this evening holds: something very ordinary or something unusual. Whatever it is, I’ll be keeping these reflections in mind. Over time, they help us meet new experiences with greater clarity, more sure of who we are. That’s my hope anyway.